“The only kind of writing is rewriting.” – Ernest Hemingway

A lot of new writers don’t take that quote seriously enough. The University System – in particular – encourages the “one draft wonder.” Those of us who went through that system quickly developed a sense that, if you can’t get it right the first time you won’t get it right at all. But the more you write and the better you get, the more you begin to feel the truth of Hemingway’s words at a bone-level. No one can get it right in a single pass. Not even industry legends.

With that in mind, as promised, this post is going to delve into two different versions of a scene in one of the most beloved action films of all time: Raiders of the Lost Ark. The first comes from Lawrence Kasdan’s third draft. It’s available online, and I’ll place a link for it at the bottom of this post. The second is the version that appears in the final film.

Before we get started, however, I want to remind you of a point I made in my last post: The Problem of Exposition. If you haven’t read it, I highly recommend going back and giving it a look-see before starting on this one. For those who are not inclined to do so, or for those who have read it but need a reminder, here’s the most important point:

Exposition, or laying pipe, is best done through conflict rather than shoe-horning it in through dialogue or narration.

Got that? Cool, on to the main event.

In this scene, Indiana Jones arrives at a bar in Nepal, searching for his old friend Abner Ravenwood, and for a vital clue to the resting place of the Lost Ark of the Covenant. Instead, he finds Abner’s daughter Marion.

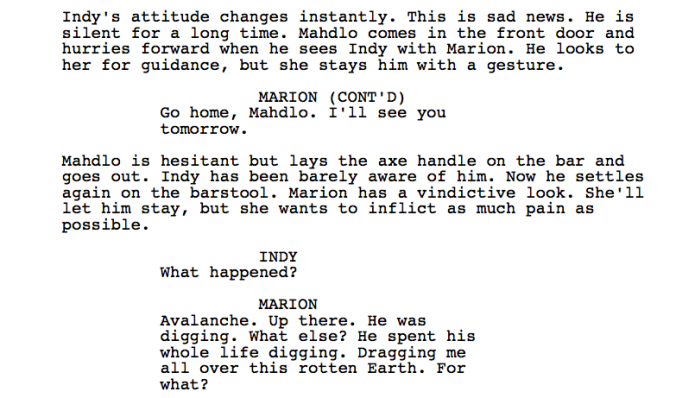

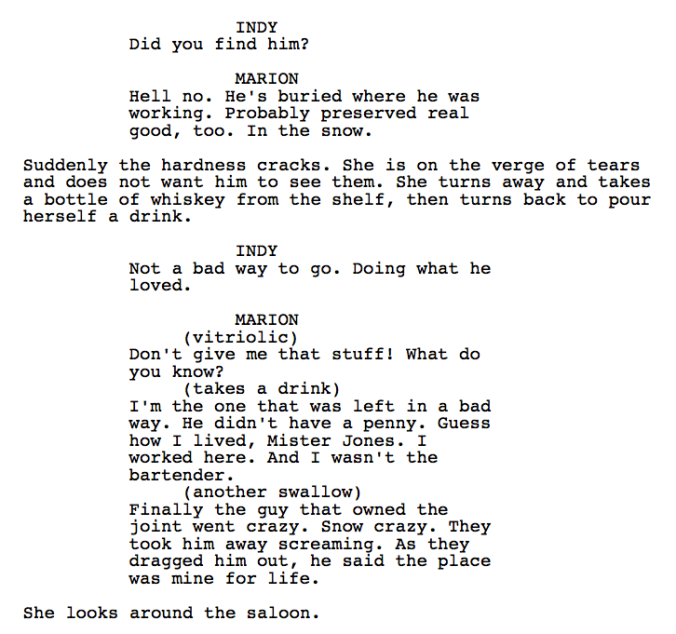

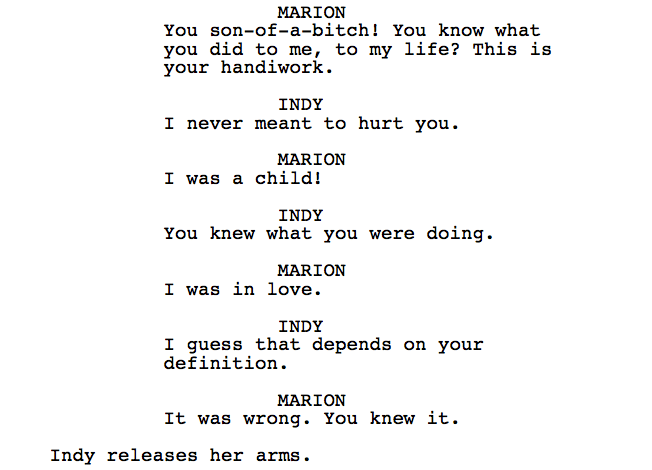

In both versions, the scene begins with Marion ordering the bar’s patrons to clear out. But, in the first version, one patron refuses to leave-

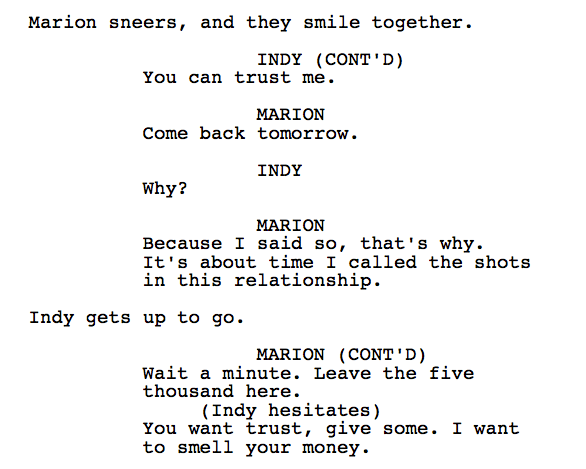

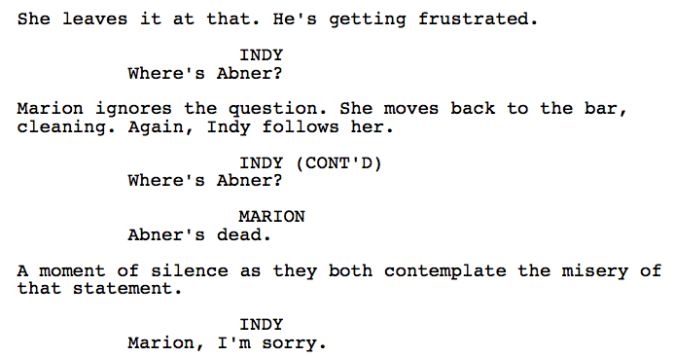

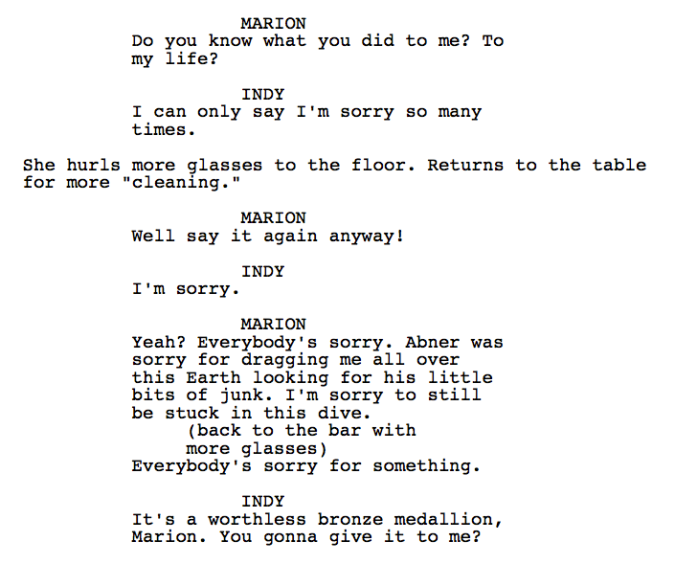

Draft Three

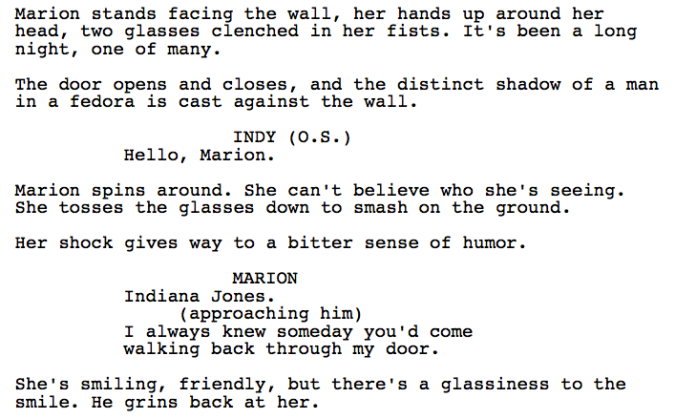

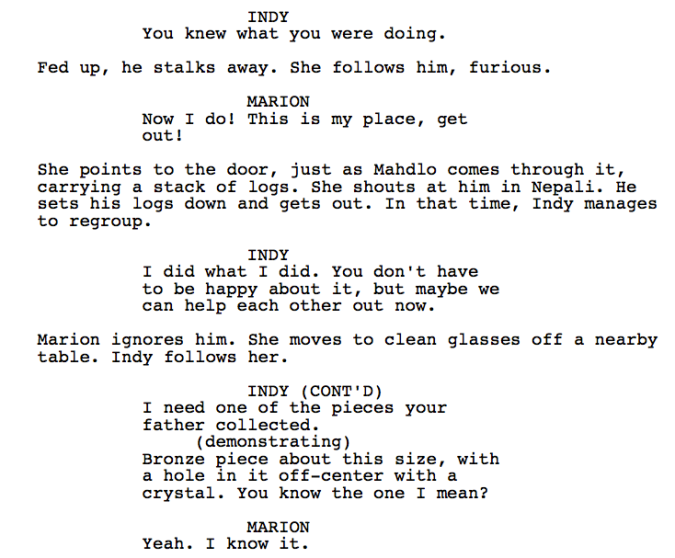

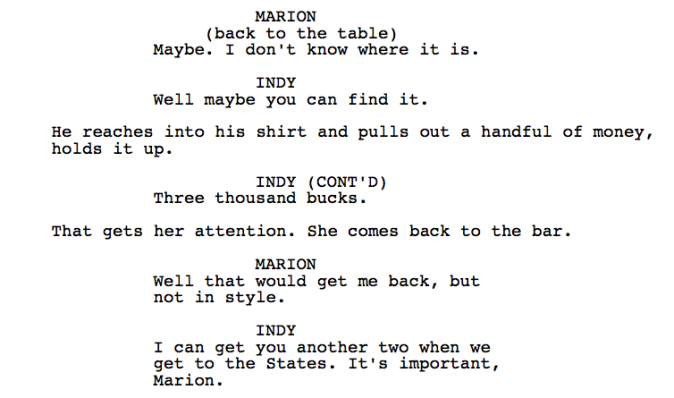

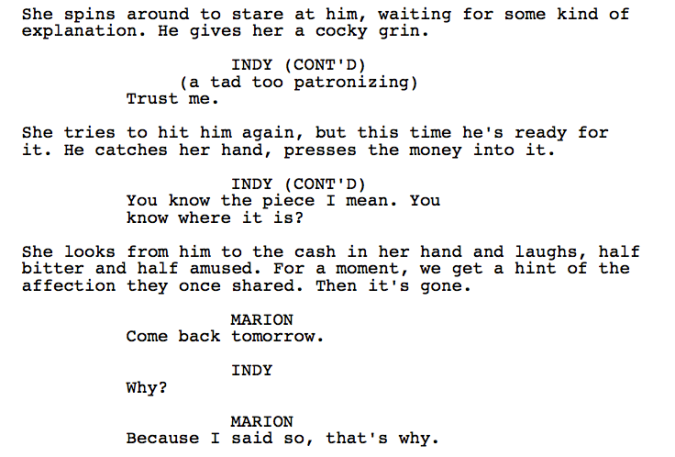

Final Version

Now take a look at this clip on Youtube of the same scene in the final film. I’ll also include a transcription I made in case you’d rather not compare Crab Apples to Granny Smiths.

Comparison

So, what do you notice about these two different versions of the same scene? We’ll start with Economy, then move on to Exposition, and finally come around to Character Development.

Economy

This is an easy one. The final version that appears in the film is half the length of the one in the third draft. Now, shorter isn’t always better. After all, no one is going to say that reading the sentence – “Indiana Jones and Marion Ravenwood battled Nazis to find the Ark of the Covenant, only for the US Government to take possession of it” – is better than watching the full film. That said, in most cases a shorter version of a scene will be superior to a longer one. This has nothing to do with the length, and everything to do with the concentration of action in the scene.

Both versions of this scene cover the same amount of narrative ground, but the final version covers it twice as fast as the draft version. The same action is condensed into a concentrated form. The result is a much more intense and engaging scene.

Exposition

Here we get to the reason I decided to write this post. This point flows directly out of Economy, because most of the additional content that was cut from the draft to make the final version as tight as it is came from unnecessary exposition.

Remember that exposition works best when it emerges from conflicts between characters.

In the draft version we get the following points of exposition:

- Marion is Abner Ravenwood’s daughter

- Abner died.

- He died in an avalanche and the body was never found.

- Marion survived in the meantime by prostituting herself.

- She ended up running the bar when the old owner went insane.

- She’s not happy there and wants to go back to the States, but she needs a lot of money to do it – at least to go back in style the way she wants to. She doesn’t know where she’s going to get it.

- Marion and Indy once had an affair. It is implied that she was underaged. She was certainly young and naive. She blames him for her current circumstances, presumably because he left and never came back. But she still has feelings for him.

That’s seven bits of information that we get in as many screenplay pages (which ought to translate to roughly seven minutes of screen-time).

The structure of the scene happens in phases:

First, we get the expositional dialogue. Marion and Indy literally talk through all of the points above, crossing them off in conversation with only a thin veneer of conflict to tie things together. It’s basically a check-list.

Next, we get a mention of the plot conflict that brings Indy here and how Marion relates to it (the medallion), before taking off with the personal conflict between them (i.e. They had an affair of some kind when she was younger, he left her, she resents him bitterly but also still has feelings for him, so they argue).

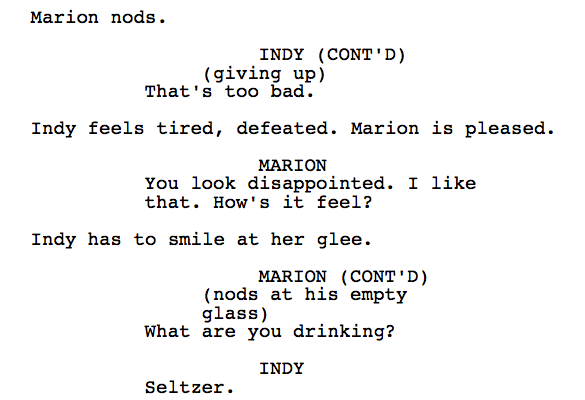

Finally, as the personal conflict winds down, the plot conflict reemerges as the dominant force in the scene. They make a deal. We get a brief resurgence of the personal conflict as Marion demands a kiss, and Indy leaves.

I’ll get to the Character Development angle on all of this in the next section. For now we’re just focused on the delivery of Exposition, which is comparatively sloppy in this earlier draft.

It’s all handled upfront, effectively a “close your eyes and swallow the pill” scenario. That in and of itself adds to the length of the scene, because it means there needs to be whole extra section there exclusively for information. Worse, there is no conflict to drive that information, which means that the interactions between the characters are broken down by factoids rather than story beats. Put simply, the story stalls for several pages while the two characters vomit up the information we theoretically need to understand the story.

But, clearly, not all of that exposition is necessary. Take a look at the following three points:

- Abner died in an avalanche and the body was never found

- Marion survived in the meantime by prostituting herself

- She ended up running the bar when the previous owner went insane

None of these have much to do with the story and the conflicts at hand.

- Abner is a character we never meet, and who we only hear about incidentally. We therefore don’t much care how he died, or what happened to his body.

- Marion’s survival in between Abner’s death and Indy’s arrival does not have direct bearing on the story. That’s a point that could have made it in as ammunition to be hurled at Indy in their fight, but as exposition it’s irrelevant.

- Similarly, there’s no story reason to tell us how she ended up running the bar. We only need to know that she’s there, she doesn’t like it, and she can’t get out without more cash than she can currently lay her hands on.

The final version of the scene quite rightly cuts all three of these pieces of information out. All they do is slow things down, diverting the audience’s attention from the facts and the events that do have real bearing on the events of the film.

The final version therefore has a little over half as many points of exposition to deliver. Moreover, its structure is designed to fold that information much more seamlessly into the scene’s real conflicts.

The scene begins with Indy walking in, all swagger. He tries to set things off with the plot conflict, asking about the item that Abner collected.

Significantly, he says: “I need one of the pieces your father collected.” On its surface, that’s a simple declaration of desire, a line drawn in the sand. He wants this thing; it’s his goal in this scene. But when he says, “your father,” he is also eliminating the need for any additional dialogue tying Marion and Abner together. We now know the relationship between those two, and it didn’t take any extra exposition to draw it out.

Marion, however, doesn’t give a damn about the film’s central plot at this point. She has a personal conflict to pick with Indy, and she immediately hijacks control of the scene by walloping him across the jaw.

They argue, and in the course of that argument they use facts from their shared past against one another. The conflict is driving this dialogue, not the information.

Nothing is stated directly. And nothing is said with the sole intention of informing. We learn the backstory almost as an incidental feature of witnessing a moment of conflict between these two characters. As a result, it all feels smooth and effortless, practically below the level of conscious thought.

From there, Indy tries to bring the conversation back to the story’s main conflict. Marion doesn’t cooperate, and so Indy asks after Abner in the hopes that he will prove more willing to help.

Only, it turns out Abner is dead, which is Marion’s lever to bring the personal conflict back into the foreground. Again, the exposition becomes ammunition for the characters in their conflict. Indy seeks to use Abner to get what he wants, but instead Marion does (Yes, I know ‘use’ is too calculating a term here. She’s not thinking, “Ooh, I can use my dead dad as leverage.” But Indy bringing him up when he does changes the fact of Abner’s death from mere exposition to a key factor in the scene’s shifting balance of power).

Indy brings up the medallion and the film’s central plot again, but this time he introduces something that Marion needs: money. The central plot conflict and the personal conflict thereby snap back together, because both characters now have a vested interest in the same conversation.

We then learn about Marion’s desire to go back to the States as “a goddamn lady,” when she refuses the initial price he offers: “That will get me back, but not in style.” She doesn’t say why she wants to go back in style. She doesn’t need to.

All of the vital points of exposition from the earlier draft thereby make it into the final scene, but they are presented in a subtler and pithier way. Put simply, the information is made to serve the scene, the characters, and the conflicts between them, not the other way around.

Character Development

Finally, I’d like to say a brief word about character development in the two versions of this scene.

In the draft version, we are presented with two rather flat characters. The Indiana Jones we see here is not the Indiana Jones we know and love. He’s too calm, too in control, too bland. The quintessential uncomplicated tough guy, like James Bond, Conan the Barbarian, or a dozen other pulp heroes.

Marion is an equal cliché, summed up when Indy calls her – to our cringing sensibilities – a “tough broad.” She brings to mind all of the two-dimensional women we find in the old hard-boiled novels: a hard shell protecting a soft heart.

The final version of the scene presents us with the characters as we know them. For a fuller rundown of my thoughts on Indy, see my earlier post on The Curious Case of Indiana Jones. In the meantime, let’s just say that Indy thinks he’s an unflappable pulp hero, but he’s more characterized by his weaknesses than his strengths.

When it comes to Marion, the character we see in the final scene is – despite being less complex in terms of backstory and having spent a shorter time onscreen – rather interesting and multifaceted. She’s a woman who finds herself in a rut with no way out, life refusing to break her way, and who finds her past suddenly showing up to haunt her. Despite that, she is able to stand her ground and hold out for what she wants. But, more importantly, we get the distinct impression throughout the scene that she, like any real human being, only reveals half of what she’s thinking. Between the earlier draft and this version, she goes from a two-dimensional cliché to a character with real depth.

The key lesson in that is that informational complexity does not equate to strong characters. If not used carefully, sweeping backstories actually get in the way of character development. Subtext and conflict do far more to make a character multifaceted than brute exposition ever could.

Conclusion

And that brings us to the end of my argument. I’d like to thank you for sticking with me all the way through this monster of a post. I promise to make the next one shorter.

It’s my hope that you will come away from this feeling inspired to go out there and write. The improvements we see between the draft version of the script for Raiders of the Lost Ark and the final version are immense. And remember that the version I found online was already the third draft of the script. There were two that came before it, and who knows how many that came after it. The truth is that no work of art worth experiencing was ever made without revision, often drastic revision. So, whether you consider yourself a screenwriter, a novelist, or just a bungling amateur with an idea you can’t shake, get out there and write something. Then rewrite.

As promised, here‘s the link to the full third draft of Raiders of the Lost Ark. I have to warn you, it’s really different.