You’re watching Princess Mononoke, a Japanese animation from the same creators as Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle. Japanese it may be, but it’s still an animation, right? Still a kids movie. The main character shoots an arrow, and you prepare for it to either miss or bounce harmlessly off the target’s armor. You know that something will happen to shelter children from the realities of death. Instead, the arrow hits, and the target’s head pops clean off his shoulders. Death.

For an American audience watching that scene, the violence it depicts poses a problem of classification. We are used to thinking of animations as kids movies, although many of the people who go to see animated movies are actually in their twenties (which is of course a topic for another day). But, at the same time, we’re used to thinking of kids movies as clean and innocent. Filmmakers purge them of issues and images that we view as too grown-up for children: sex, violence, sacrifice, death and loss. A movie, like Mononoke, that challenges those expectations in an animated format therefore seems unusual, fresh, and even a little edgy.

We could attribute this edginess to the fact that the film is Japanese. Maybe standards are different in Japan. Maybe animations there are aimed at adult audiences. Maybe the issues kids are thought mature enough to wrestle with are simply different in Japan. That question itself, however, invites us to examine the animated films produced in our own culture.

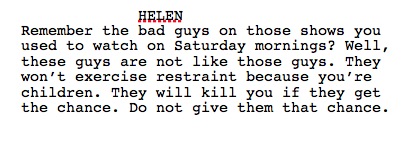

Surprisingly, the best animated films produced in the West do not stray too far from Mononoke’s mark. I’m not talking about recent Disney films like Frozen and Moana, which follow the kiddie pattern to a fault. But you don’t have to go that far back to find something like The Incredibles, which, when you strip away its superhero bells and whistles, is about a mid-life crisis. Why aim a story about a mid-life crisis at kids? They’re still in the middle of their early-life crisis (don’t ask me when life stops being a crisis; I’ll let you know when I get there). More than that, the film addresses issues like adultery, betrayal, death and violence. Take a look at the following speech one of the characters gives:

This is more than a clever speech written for one of the characters. It tells us something about the world of the film, and how it differs from the worlds of similar films. Simply put, the issues on the screen are going to be real adult issues, despite being marketed at children. And because of that, even if the kids watching miss the little references to adultery, there is a sense of reality and danger to the world of the film that most kids stories can’t come close to emulating.

The same is true, to a greater or lesser extent, for all of my favorite kids movies. Renaissance Disney did a particularly good job with Lion King, Beauty and the Beast, Mulan, and many others. Ratatouille incorporates its fair share of the adult world into the world of the film, although, like The Incredibles, it sometimes has these issues lurking beneath the surface (as when Colette reaches for her pepper spray after Linguini starts talking about his “little chef”). The best, most long-lasting kids films all seem to shy away from the conventional wisdom that movies for children can only address children’s themes.

A while back I read a quote from Miyazaki, the man behind Princess Mononoke, that I think brilliantly sums up the truth at the heart of this trend. I can’t find it now, and I’d love it if someone could point me in the right direction. That said, the content of the quote was as follows:

Children’s stories try too hard to cater to children. And in so doing they miss the issues that children actually care about, because the issues children actually care about are the same issues adults care about. Children are not ignorant of death, or hardship, or the darker content of the world. What they lack are the tools and experiences needed to process these ideas on their own.

And that’s where stories come in. Stories serve as a framework for kids to lay to rest the real things that go bump in the night; they help kids process. So, when a kids’ story refuses to address its audience’s real-world questions, it fails. If the makers of kids’ movies want to earn the trust of both children and parents, they cannot coddle their audience. Instead, they ought to treat kids like what they are: little grownups.